Hector F. Rios

Department of Periodontics & Oral Medicine, School of Dentistry,

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

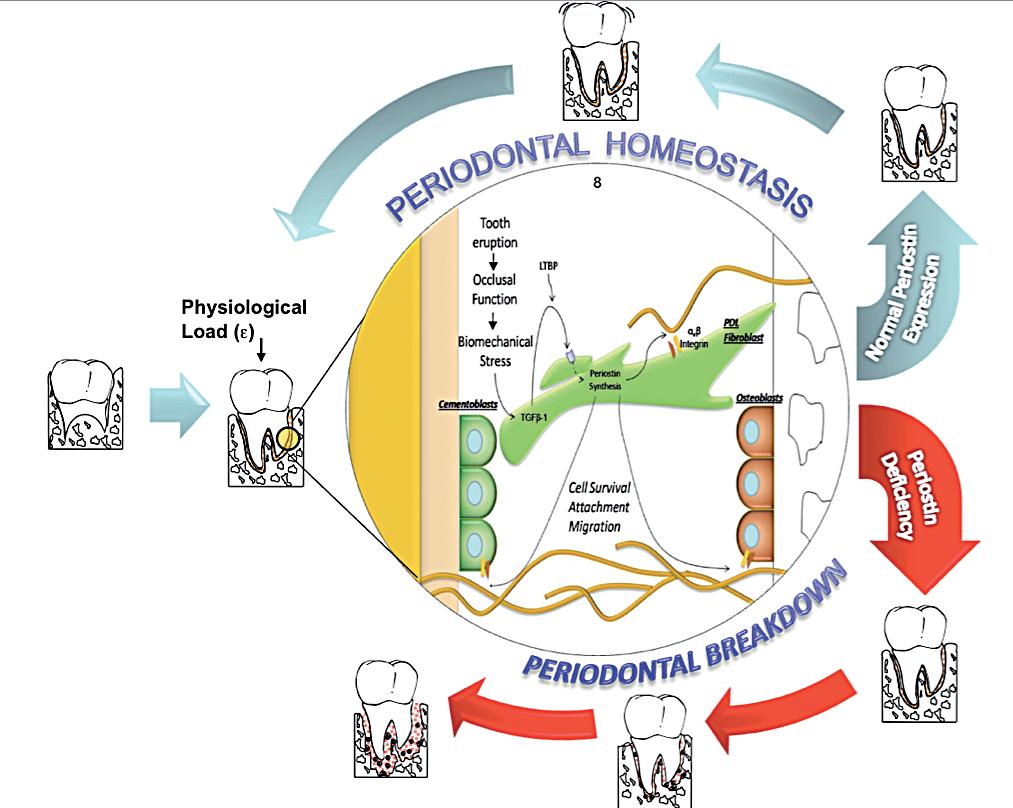

Periodontal diseases are a possible modifiable risk factor for morbidity and mortality in several systemic diseases1-4 with an obvious impact in the patient’s quality of life5,6. Collectively, they afflict over 80% of adults worldwide and approximately 13% displaying severe disease concomitant with early tooth loss7. In periodontitis, the detrimental changes that the tooth-supporting tissues undergo are primarily the result of specific microbial challenges8-10. These challenges in a susceptible host disrupt the functional and structural integrity of the tooth supporting apparatus11. It is known that the structure and properties of the periodontal tissues are intimately related by crucial cell-matrix interactions12-16. However, the mechanisms by which these microorganisms undermine and compromise the modulation of these synergistic events are not clearly understood. The proper regulation of these interactions in a mechanically dynamic environment, such as in the periodontium, determines the adaptive dentalalveolar response by orchestrating the function of important bioactive proteins such as growth factors, cytokines and proteases (Figure 1)17-20. The proteins modulating these interactions are known collectively as matricellular molecules21-24. The purpose of this review is to present and discuss the available evidence that exist regarding the matricellular molecule Periostin in the context of the periodontium.

What is Periostin?

Periostin is a disulfide-linked 90 kDa secreted protein of relatively unknown function that has homology with the insect’s central nervous system protein fasciclin-I and is highly conserved among higher organisms25. The protein is highly homologous to βig-h3, a molecule induced by TGF-β that promotes the adhesion and spreading of fibroblasts. Therefore, Periostin is thought to function as an adhesion molecule during bone formation and can support osteoblastic cell line attachment and spreading26. Purified recombinant Periostin has been shown to be a ligand for αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins, promoting integrin-dependent cell adhesion and motility27. Multiple reports have also demonstrated elevated Periostin levels in neuroblastoma28, epithelial ovarian cancer27 and in non-small cell lung carcinoma29 that have undergone epithelial mesenchymal transformation (EMT) and metastasized. Moreover, it has been shown that Periostin potently promotes cell survival via the Akt/PKB pathway30. It has also been associated with extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition following myocardial infarction and has been reported to be essential for healing after acute myocardial infarction31,32.

Why Periostin?

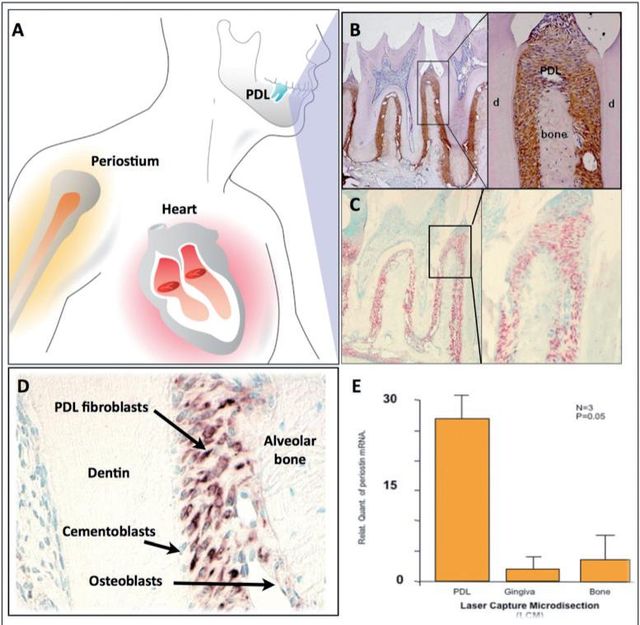

Previously, it has been shown that Periostin is expressed in the developing teeth at sites of epithelialmesenchymal interaction, which suggests that Periostin could play multiple roles as a primary responder molecule during tooth development and may be linked to deposition and organization of other ECM adhesion molecules during maintenance of the periodontium33. Periostin mRNA has been found to be negatively regulated by Epidermal Growth Factor and 1,25-(OH)2 D3 and upregulated by TGF-β1 and BMP- 225,26,34. Interestingly, immunohistochemical analysis has shown that, in adult mice, Periostin protein is preferentially localized in the periosteum and PDL26, suggesting potential roles in the maintenance and remodeling of these structures. Of all the known proteins that have been found to be expressed in the PDL, Periostin has been the one that shows greater specificity. For this reason, Periostin is commonly used as a marker for the PDL. Periostin, within the periodontal context, is expressed specifically by PDL fibroblasts, suggesting a potential role in PDL function26,33 (Figure 2). Recently, it was reported that Periostin promoter activities were enhanced by overexpression of Twist, resulting in increased Periostin expression in vitro35. In addition, in vivo, Twist and Periostin have been found to be co-expressed and intimately regulated by changes in the occlusal force36which led researchers to postulate Twist as a Periostin transcription factor. Interestingly, Periostin has shown to present a divergent distribution during orthodontic tooth movement; it is upregulated in the areas of compression and down regulated in the areas of tension37. Furthermore, immunoelectron microscopic observation of the mature PDL verified the localization of Periostin between the cytoplasmic processes of periodontal fibroblasts and cementoblasts and the adjacent collagen fibrils38. Its expression has been reported to influence cell behavior as well as collagen fibrillogenesis39. Therefore, it may exert control over the structural and functional properties of PDL tissues in health and disease.These findings suggest that Periostin is present at the sites of the cell-to-matrix interaction, serving as an adhesive factor for bearing mechanical forces, including occlusal force.

Is Periostin necessary for normal periodontal function?

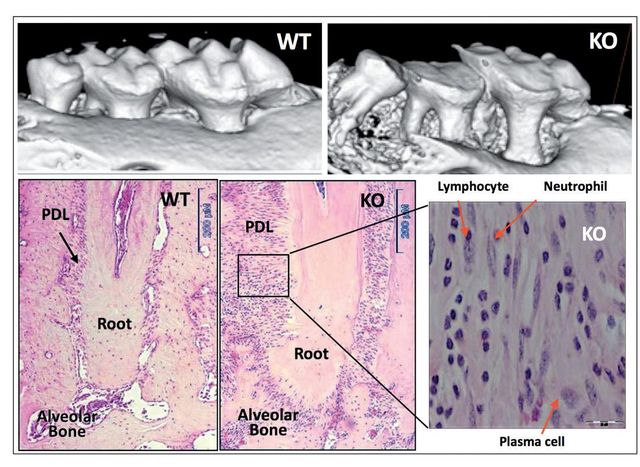

We provided initial evidence of the essential role of Periostin in the functional and structural integrity of the periodontium40. Periostin-deficient animals clearly show severe deterioration of the tooth supporting structures40,41. Our work demonstrated that in the context of Periostin deletion, the periodontium rapidly deteriorates over time and is unable to sustain the physiologic mechanical stimulus. Thereby, deeming this molecule as necessary for PDL function and, therefore, for proper periodontal integrity (Figure 3). Furthermore, we have shown that Periostin is specifically necessary during occlusal function, and that in the case of the Periostin KO mice, the periodontal ligament is unable to sustain the normal physiologic occlusal load, which results in a traumatic stimulus to the periodontium. While the literature suggests that primary occlusal trauma leads to an adaptive response where no destruction of the supporting tissues occurs, in the Periostin KO the mechanical stimulus can be classified as a secondary trauma that, due to the Periostin deficiency, causes a detrimental effect in the periodontium. This leads to severe alveolar bone loss, severe clinical attachment loss and significant widening of the PDL space.

What is Periostin doing in the extracellular matrix?

Periostin interacts with extracellular structural molecules, such as Collagen Type I and cell membrane proteins, such as αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins. These matricellular interactions have been reported to influence cell behavior as well as collagen fibrillogenesis6. The collagen fiber diameter is reduced in the absence of Periostin, resulting in a decrease modulus of elasticity in the KO. In addition, Periostin interaction with αvβ5 activates cell survival signaling pathways. Our group demonstrated that Periostin closely related with the PDL fiber bundles from the root surface cementum to the alveolar bone engaging the tooth supporting apparatus. Thus, in the context of Periostin deletion, the periodontium rapidly deteriorates over time and is unable to sustain the physiologic mechanical stimulus. Collectively this evidence suggests a critical role of the matricellular adaptor protein, Periostin, serving as a potential modulator of important tissue mechanical properties. Significant molecular changes have been reported to occur during periodontal disease progression. Altered levels of Transforming Growth Factorβ (TGF-β) have been implicated in periodontal disease progression42-45. TGF-β-1 reduced levels in advanced periodontal disease have been associated with altered Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMP’s) and Interleukin-1β (IL1-β) activity42,44. TGF-β-1 levels increase under mechanical strain and regulate the expression of Periostin26,41,46. These molecules are expressed at different stages of wound healing and some patterns are more transient than others. We have reported novel findings in regards to its relevance in PDL function40,41. Our data suggest that TGF-β may influence the integrity of the periodontium through the regulation of Periostin expression and function. The importance of Periostin in other specialized tissues, such as the heart, clearly highlights its importance in repair, regeneration and recovery after myocardial infarction. Periostin is normally secreted by PDL fibroblasts in response to injury, and it interacts with integrin receptors on target cells to modulate cellular and matrix remodeling. Recently, with the advances in technology and the availability of animal models, a more mechanistic model of disease pathogenesis appears feasible. From conventional deletion of periodontal “specific” genes we have identified key factors that appear to determine functional and structural stability of the supporting tissues. Mice lacking the transmembrane protein αvβ 6 integrin, a molecule constitutively expressed in the healthy junctional epithelium, lose rapid attachment and a significant apical migration of the sulcular epithelium favors the formation of periodontal pockets47. These changes are associated with altered signaling of TGFβ-1, a molecule involved in multiple regulatory functions including tissue repair and immune system. TGFβ-1 is secreted from the cell as a latent precursor complex. The secreted latent TGFβ-1 is bound to the extracellular matrix via a latent TGFβ-1 binding protein (LTBP1)48. Binding of αvβ6 integrin to the atent associated propeptide has been implicated in the activation and release of the latent TGFβ-149,50 which in turns favors extracellular matrix (ECM) formation and maturation by the regulation of MMP-8 and MMP-1342,51. The examination of tissues from advanced periodontal disease patients shows consistent changes that are characterized on one hand by decreased TGFβ-1 and αvβ6 integrin, and on the other hand by increased levels of tissue collagenases, gelatinases and proinflammatory cytokines such as IL1-β44,47,52,53. The junctional epithelium during periodontal disease is the first critical tissue barrier breached by oral bacteria. It then triggers a robust, leukocyte-mediated immunological defense reaction within the gingival tissues. This inflammatory reaction may be contained at this level or, as in the case of susceptible individuals, it may progress to compromise the PDL integrity and the alveolar bone.

Discussion

Periodontal diseases affect a large proportion of the world’s population. The identification of genetic susceptibility variants and their role on disease onset and progression has been the focus of a number of studies. Based on the evidence reviewed, Periostin represents a novel biologic agent with significant diagnostic and therapeutic potential that could ultimately enhance patient care. The available preclinical and mechanistic studies currently available in the periodontal biology field, have provided provide novel insights into the regulation of PDL function during periodontal tissue health and disease. Understanding the role of Periostin in the PDL, helps capture the dynamic nature of, the matricellular biochemical events involved in the transition between periodontal health and disease (Figure 4). This information, further contributes to the ongoing effort of describing the basic elements involved in a new model of periodontal disease pathogenesis. Such a model incorporates gene, protein, and metabolite data into dynamic biologic networks that include disease initiating, susceptibility, and resolving mechanisms. Ultimately, these data will aid in our understanding of periodontal biology relevant to cell-matrix dynamics and homeostasis. Therefore, unraveling novel pathways that determine periodontal disease susceptibility that could be targeted in the treatment of inflammatory periodontal diseases. Physiologically relevant differences in Periostin levels are yet to be determined in humans. From our animal model experiments, we reported a clear periodontal phenotype developing in the mice completely lacking Periostin (KO) while minor or no changes occurred with a 30-50% decrease in Periostin (Het). However, these observations do not reflect a chronic microbial challenge condition such as the one find in human periodontal disease. The model proposed partially addresses this issue. However, the inability to induce the formation of a complex biofilm as in human periodontitis is a clear limitation. Currently, periodontal conditions are diagnosed based on the clinical presentation of the disease. The current classifications guides us to identify “different” forms of the disease that manifest themselves with a common clinical presentation and cluster them within groups (i.e., chronic, aggressive, necrotizing, etc). Therefore, it is our responsibility to acknowledge the complexity and heterogeneity of this group of conditions. The limitation of the lack of an etiology-based classification compromises the accuracy of a specific diagnosis and, therefore, the identification of the most appropriate therapy. Further studies should be geared to identify underlining conditions, such as Periostin expression, that may be associated with an increase rate and extent of periodontal breakdown.

Acknowledgements

The Authors appreciate Chris Jung for assisting with the preparation of the figures. This work was supported by the National Institute of Health/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research grants NIH/NIDCR K23DE019872 (HFR).

Correspondence

Hector F. Rios

Department of Periodontics and Oral Medicine

University of Michigan, School of Dentistry 1011 N. University, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1078

Tel. 734-763-3383 - Fax: 734-936-0374 - hrios@umich.edu

References

1. Grossi SG, Genco RJ. Periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus: a two-way relationship. Annals of periodontology / the American Academy of Periodontology 1998;3:51-61.

2. Persson GR, Persson RE. Cardiovascular disease and periodontitis: an update on the associations and risk. Journal of clinical periodontology 2008;35:362-379.

3. Lin D, Moss K, Beck JD, Hefti A, Offenbacher S. Persistently high levels of periodontal pathogens associated with preterm pregnancy outcome. Journal of periodontology 2007;78:833-841.

4. Boehm TK, Scannapieco FA. The epidemiology, consequences and management of periodontal disease in older adults. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939) 2007;138 Suppl:26S-33S.

5. Cunha-Cruz J, Hujoel PP, Kressin NR. Oral health-related quality of life of periodontal patients. Journal of periodontal research 2007;42:169-176.

6. Needleman I, McGrath C, Floyd P, Biddle A. Impact of oral health on the life quality of periodontal patients. Journal of clinical periodontology 2004;31:454-457.

7. Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet 2005;366:1809-1820.

8. Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RL Jr. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. Journal of clinical periodontology 1998;25:134-144.

9. Socransky SS, et al. Use of checkerboard DNA-DNA hybridization to study complex microbial ecosystems. Oral microbiology and immunology 2004;19:352-362.

10.Loesche WJ, Syed SA, Stoll J. Trypsin-like activity in subgingival plaque. A diagnostic marker for spirochetes and periodontal disease? Journal of periodontology 1987;58:266-273.

11.Dzink JL, Tanner AC, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Gram negative species associated with active destructive periodontal lesions. Journal of clinical periodontology 1985;12:648-659.

12.Takahashi I. et al. Expression of genes for gelatinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in periodontal tissues during orthodontic tooth movement. Journal of molecular histology 2006;37:333-342.

13.Gotz W, Heinen M, Lossdorfer S, Jager A. Immunohistochemical localization of components of the insulin-like growth factor system in human permanent teeth. Archives of oral biology 2006;51:387-395.

14. Lee A, Schneider G, Finkelstein M, Southard T. Root resorption: the possible role of extracellular matrix proteins. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2004;126:173-177.

15. Reichenberger E, et al. Collagen XII mutation disrupts matrix structure of periodontal ligament and skin. Journal of dental research 2000;79:1962-1968.

16. Gao J, Jordan TW, Cutress TW. Immunolocalization of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in human periodontal ligament (PDL) tissue. Journal of periodontal research 1996;31:260-264.

17. Yang YQ, Li XT, Rabie AB, Fu MK, Zhang D. Human periodontal ligament cells express osteoblastic phenotypes under intermittent force loading in vitro. Front Biosci 2006;11:776-781.

18. Tsuji K, Uno K, Zhang GX, Tamura M. Periodontal ligament cells under intermittent tensile stress regulate mRNA expression of osteoprotegerin and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloprotease-1 and -2. Journal of bone and mineral metabolism 2004;22:94-103.

19. Sato R, Yamamoto H, Kasai K, Yamauchi M. Distribution pattern of versican, link protein and hyaluronic acid in the rat periodontal ligament during experimental tooth movement. Journal of periodontal research 2002;37:15-22.

20. Long P, Liu F, Piesco NP, Kapur R, Agarwal S. Signaling by mechanical strain involves transcriptional regulation of proinflammatory genes in human periodontal ligament cells in vitro. Bone 2002;30:547-552.

21. Kyriakides TR, Bornstein P. Matricellular proteins as modulators of wound healing and the foreign body response. Thrombosis and haemostasis 2003;90:986-992.

22. Bornstein P, Sage EH. Matricellular proteins: extracellular modulators of cell function. Current opinion in cell biology 2002;14:608-616.

23. Bornstein P. Matricellular proteins: an overview. Matrix Biol 2000;19:555-556.

24. Bornstein P. Diversity of function is inherent in matricellular proteins: an appraisal of thrombospondin 1. The Journal of cell biology 1995;130:503-506.

25. Takeshita S, Kikuno R, Tezuka K, Amann E. Osteoblast-specific factor 2: cloning of a putative bone adhesion protein with homology with the insect protein fasciclin I. The Biochemical Journal 1993;294 (Pt 1):271-278.

26. Horiuchi K, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel protein, periostin, with restricted expression to periosteum and periodontal ligament and increased expression by transforming growth factor beta. J Bone Miner Res 1999;14:1239-1249.

27. Gillan L, et al. Periostin secreted by epithelial ovarian carcinoma is a ligand for alpha(V)beta(3) and alpha(V)beta(5) integrins and promotes cell motility. Cancer research 2002;62:5358-5364.

28. Sasaki H, et al. Expression of the periostin mRNA level in neuroblastoma. Journal of pediatric surgery 2002;37:1293-1297.

29. Sasaki H, et al. Serum level of the periostin, a homologue of an insect cell adhesion molecule, as a prognostic marker in nonsmall cell lung carcinomas. Cancer 2001;92:843-848.

30. Bao S, et al. Periostin potently promotes metastatic growth of colon cancer by augmenting cell survival via the Akt/PKB pathway. Cancer cell 2004;5:329-339.

31. Dorn GW 2nd. Periostin and myocardial repair, regeneration, and recovery. The New England journal of medicine 2007;357:1552-1554.

32. Shimazaki M, et al. Periostin is essential for cardiac healing after acute myocardial infarction. The Journal of experimental medicine 2008;205:295-303.

33. Kruzynska-Frejtag A, et al. Periostin is expressed within the developing teeth at the sites of epithelialmesenchymal interaction. Dev Dyn 2004;229:857-868.

34. Ji X, et al. Patterns of gene expression associated with BMP-2-induced osteoblast and adipocyte differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cell 3T3-F442A. Journal of bone and mineral metabolism 2000;18:132-139.

35. Oshima A, et al. A novel mechanism for the regulation of osteoblast differentiation: transcription of periostin, a member of the fasciclin I family, is regulated by the bHLH transcription factor, twist. Journal of cellular biochemistry 2002;86:792-804.

36. Afanador E, et al. Messenger RNA expression of periostin and Twist transiently decrease by occlusal hypofunction in mouse periodontal ligament. Archives of oral biology 2005;50:1023-1031.

37. Wilde J, Yokozeki M, Terai K, Kudo A, Moriyama K. The divergent expression of periostin mRNA in the periodontal ligament during experimental tooth movement. Cell and tissue research 2003;312:345-351.

38. Suzuki H, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of periostin in tooth and its surrounding tissues in mouse mandibles during development. The anatomical record 2004;281:1264-1275.

39. Norris RA, et al. Periostin regulates collagen fibrillogenesis and the biomechanical properties of connective tissues. Journal of cellular biochemistry 2007;101:695-711.

40. Rios H, et al. Periostin null mice exhibit dwarfism, incisor enamel defects, and an early-onset periodontal disease-like phenotype. Molecular and cellular biology 2005;25:11131-11144.

41. Rios HF, et al. Periostin is essential for the integrity and function of the periodontal ligament during occlusal loading in mice. Journal of periodontology 2008;79:1480-1490.

42. Yan C, Boyd DD. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase gene expression. Journal of cellular physiology 2007;211:19-26.

43. Atilla G, Emingil G, Kose T, Berdeli A. TGF-beta1 gene polymorphisms in periodontal diseases. Clinical biochemistry 2006;39:929-934.

44. Agarwal S, et al. Regulation of periodontal ligament cell functions by interleukin-1beta. Infection and immunity 1998;66:932-937.

45. Skaleric U, Kramar B, Petelin M, Pavlica Z, Wahl SM. Changes in TGF-beta 1 levels in gingiva, crevicular fluid and serum associated with periodontal inflammation in humans and dogs. European journal of oral sciences 1997;105:136-142.

46. Hamilton DW. Functional role of periostin in development and wound repair: implications for connective tissue disease. Journal of cell communication and signaling 2008;2(1-2):9-17.

47. Ghannad F, et al. Absence of alphavbeta6 integrin is linked to initiation and progression of periodontal disease. The American journal of pathology 2008;172:1271-1286.

48. Taipale J, Miyazono K, Heldin CH, Keski-Oja J. Latent transforming growth factor-beta 1 associates to fibroblast extracellular matrix via latent TGF-beta binding protein. The Journal of cell biology 1994;124:171-181.

49. Annes JP, Chen Y, Munger JS, Rifkin DB. Integrin alphaVbeta6-mediated activation of latent TGF-beta requires the latent TGF-beta binding protein-1. The Journal of cell biology 2004;165:723-734.

50. Munger JS, et al. The integrin alpha v beta 6 binds and activates latent TGF beta 1: a mechanism for regulating pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Cell 1999;96:319-328.

51. Kiili M, et al. Collagenase-2 (MMP-8) and collagenase-3 (MMP-13) in adult periodontitis: molecular forms and levels in gingival crevicular fluid and immunolocalisation in gingival tissue. Journal of clinical periodontology 2002;29:224-232.

52. Gemmell E, Seymour GJ. Immunoregulatory control of Th1/Th2 cytokine profiles in periodontal disease. Periodontology 2000 2004;35:21-41.

53.Silva N, et al. Characterization of progressive periodontal lesions in chronic periodontitis patients: levels of chemokines, cytokines, matrix metalloproteinase-13, periodontal pathogens and inflammatory cells. Journal of clinical periodontology 2008;35:206-214.

[…] >English Version> […]