1DMD, Clinical Assistant Professor, New York University College of Dentistry

2DDS

The goal of this article focuses on how to restore patients who have severe loss of function and aesthetics. The patient, a 55-year-old male, presents with the chief complaint: “I came to get looked at and see what could be done for my teeth”. The patient initially presents with multiple broken and missing teeth (Figure 1). Past medical history is positive for seasonal allergies, Crohn’s disease, high cholesterol, osteoporosis, and thyroid disorder. The patient has no known drug allergies and has been taking aspirin (81 mg) for fi ve years as ordered by his primary physician. The extra-oral exam reveals an altered facial profi le. The lips appear thin and fl attened as if crunched. The chin has moved forward and upward. The mouth has lost shape and the lip lines have a reverse smile line. During the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) exam, the joints are load-tested. The centric relation position is considered obtained when the TMJ could be guided bimanually (with no sign of tension or pain) while the condyles were in their most superior anterior position within the glenoid fossa1,2. The TMJ is tested via careful palpation and transposition of its components to identify painful loci within the opening and closing of the arches. After manipulating the mandible into centric relation, it is realized that the patient has suffi cient interarch space to restore the patient to comfortable vertical dimension of occlusion.

Centric relation is needed to be verifi ed because it is the reproducible position utilized to restore a functional dentition3.Three main factors must be analyzed to establish a proper occlusal vertical dimension, according to Vierheller. These are: 1) the rest position, 2) the free-way space (interocclsual distance), 3) the vertical dimension of occlusion4. The vertical dimension at rest is analyzed using the act of swallowing as a guide to the physiologic rest position of the mandible5. The intraoral exam reveals an anterior impinging bite with teeth #8, 9, 10 and the mesial of tooth 11 contacting the mandibular anterior alveolar ridge. Clinical examination reveals missing maxillary teeth #5, 6, 7, 12, 13 (Figure 2) and mandibular teeth #17, 18, 19, 20, 23, 24, 25, 26, 29, 30, 31, and 32. Teeth #11 and 22 exhibit severe wear facets into pulpal chambers, but contact each other at an edge-to-edge position (Figure 3).

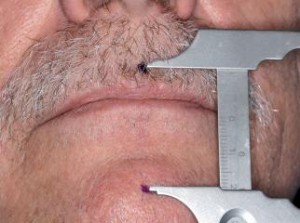

When guided into a functional centric relationship as defi ned by Dawson, the mesial marginal ridges of tooth #4 makes contact with the distal aspect of tooth #28 (Figure 4). The mandibular alveolar ridges are atrophic bilaterally (Figure 5). Both radiographic and clinical examination of the remaining teeth show advanced periodontal disease. There are many dental issues that must be addressed for this case. Certain posterior teeth with defective marginal seal of old amalgam restorations must be replaced. The remaining anterior teeth have wear facets associated with the collapsed vertical dimension of occlusion because of the lack of bilateral mandibular posterior occlusion. As a result, the maxillary dentitions have begun to drift vertically (supraerupted). There are two root tips with radiographic apical pathology compounded with gingival inflammation. The mandibular anterior gingiva is traumatized particularly in the anterior due to the severe abrasion of the lower incisors to the gingival level. Once medical and dental history examinations are evaluated, three sets of alginate impressions are made: 1) existing master casts, 2) diagnostic wax-up casts, 3) working casts. On the following visit, maxillary records are obtained via a Hanau facebow registration (Whip Mix Corp., Louisville, KY, U.S.A.). Two marks are placed on the patient’s face. The first mark is located above the upper lip and the second one is marked below the lower lip (Figure 6).

The rest position is recorded by measuring the patient’s vertical dimension between two points after the act of swallowing. The vertical dimension of rest is established at this point after consistency is achieved and the dimension is recorded using a Boley gauge caliper (Rudolf Manz GmbH & Co. KG, Germany). The height of both maxillary and mandibular occlusal wax rims are adjusted until the same vertical dimension of rest is established. Then the mandibular occlusal wax rim is reduced by 3 mm to establish a tentative occlusal vertical dimension. A study by Ward and Osterholtz presents an average of 2.78 mm of interocclusal distance using an indirect technique and an average of 3.5 mm using

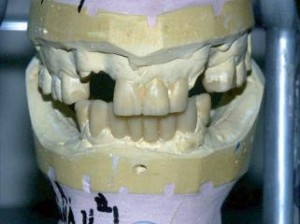

a direct technique. A fabricated Triad occlusal wax rim (Dentsply Prosthetics, York, PA, U.S.A.) is utilized with GC pattern resin (GC America Inc., Alsip, IL, U.S.A.) for a centric relation record. This centric relation record will be used to restore the vertical dimension of occlusion. The maxillary cast is then mounted using a Hanau semi-adjustable articulator (Whipmix Corp., Louisville, KY, U.S.A.), and sent to a dental laboratory with a prescription authorization for a wax-up of the anterior teeth that are broken or missing (Figure 7) and of the posterior teeth setup at the “restored” vertical dimension of occlusion. These diagnostic aides are used to formulate treatment plans to be presented to the patient.

Treatment plan

The accepted treatment plan is extraction of teeth #6, 11, 24, 25, and 26 (non-restorable), followed by initial maxillary and mandibular scaling and root planning. Root canal therapy is needed for tooth #22, coupled with a prefabricated post and core build-up material and a surveyed metal ceramic restoration. Crowns will be fabricated for teeth #21, 22, 27 and 28 as well as #8, 9, and 10 (#21 and 28 will have semi-precision attachments). The maxillary dentition will receive a maxillary Kennedy Class III, Modification I removable partial denture following the fabrication of fixed partial dentures for teeth #8, 9, and 10. Teeth #2 and 3 will have a lab-processed restoration (gold onlays with rest seat) following caries excavation and sedation. After caries excavation, the patient will have an endodontic referral for a prognosis of the teeth. Teeth #15 and 16 require a Class I posterior composite restoration (3M ESPE Z100, St. Paul, MN, U.S.A.). The final restoration for the mandibular dentition will be a fixed partial denture from tooth #21 through tooth 28 in combination with a semi-precision Kennedy Class I removable partial denture.

Treatment sequence

It is important to remind the patient before starting any treatment plan that the rehabilitation process will be long and arduous, requiring both patient patience and a strong commitment. During the first treatment session, the extraction of teeth #24, 25, 26 and root tips #6 and 11 under local anesthesia (Lidocaine HCl with epinephrine 1:100,000, Graham Chemical Co., Barrington, IL, U.S.A.) is performed and 4-0 chromic gut sutures are placed. The patient is then given time to recuperate. At the second visit, non-surgical periodontal therapy is administered on the maxillary posterior teeth, which included scaling and root planning. Oral hygiene instructions are presented at this time. On the third visit, the remaining dentitions receive periodontal therapy. On the fourth visit, root canal therapy is initiated and completed for tooth #22 in same visit. During the fifth visit, tooth #22 is prepared for a prefabricated Para-Post metal post size 4 (Coltene Whaledent, Cuyahoga Falls, OH, U.S.A.) and Ti-Core white core build-up material (Essential Dental Systems, Hackensack, NJ, U.S.A.). On this visit, teeth #21 and 22 are prepared for metal ceramic restorations using diamond burs (Brasseler, Savannah, GA, U.S.A.). The restored abutment teeth are protected with full coverage provisional restorations fabricated using

Trim II autopolymerizing acrylic (HJB Bosworth, Skokie, IL, U.S.A.) and cemented with non-eugenol TempBond, (Kerr Corp., Orange, CA, U.S.A.). At the sixth visit, teeth #27 and 28 are prepared for metal ceramic restorations using diamond burs. A lab putty index of the wax-up of fixed partial denture #21-28 is used to fabricate a provisional bridge using Trim II autopolymerizing acrylic (HJB Bosworth, Skokie, IL, U.S.A.), which is cemented using non-eugenol TempBond (Kerr Corp., Orange, CA, U.S.A.) (Figure 8). On the seventh visit, teeth #8, 9, and 10 are prepared for core build-up material and then prepared with 45-degree bevels. The abutments then are provisionalized using Biotemps (Glidewell Laboratories, Newport Beach, CA, U.S.A.) for aesthetic reasons and cemented with non-eugenol TempBond (Kerr Corp., Orange, CA, U.S.A.). This provisional restoration will serve as a guide for the fabrication of the final prostheses by evaluating the patients’ smile line, tooth form, and labial support. On the eighth visit, a secondary impression of teeth #8, 9, and 10 is made with a stock tray (Benco Dental, Wilkes-Barre, PA, U.S.A.), and a retraction cord 2 (Ultradent, Jordan, UT, U.S.A.) soaked in a hemostatic agent Hemodent (Premier Dental, Plymouth Meetings, PA, U.S.A.) is placed around the sulcus of each abutment tooth. Permadyne light-body polyether impression material (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, U.S.A.) and Impregum Penta heavy body polyether (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, U.S.A.) impression material are used to capture the optimal tooth surface and finish-line details. The impression along with work authorization is then sent to the dental verifilaboratory to begin fabrication of the final restorations. The secondary impression including the mould and shade of teeth are made and sent to the dental laboratory with a work authorization. On the ninth visit, the wax-up transitional maxillary and mandibular removable partial denture with acrylic teeth is tried in and adjustments made based on aesthetics, phonetics, and patient’s wishes. The patient returned on the tenth visit for delivery of the maxillary and mandibular transitional removable partial dentures6. On the eleventh visit, small occlusal and lingual carious lesions on teeth #14 and 15 are restored using posterior composite (3M ESPE Z100, St. Paul, MN, U.S.A.). On the twelfth visit, an impression of crowns #21 through 28 is made using a stock tray (Benco Dental, Wilkes-Barre, PA, U.S.A.). Retraction cord #2 (Ultradent, Jordan, UT, U.S.A.) soaked in Hemodent hemostatic agent (Premier Dental, Plymouth Meeting, PA, U.S.A.) is packed around teeth #21, 22, 27, and 28. Permadyne light-body polyether (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, U.S.A.) and Impregum Penta heavy-body polyether (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, U.S.A.) impression materials are used to make the final impressions. The case is then sent to the dental laboratory to begin fabrication of the final restorations. The thirteenth visit marks the start of the fabrication of semi-precision attachments. On this visit, the patient has the castings of fixed partial denture #21 through 28 to confirm seating using a GC fit checker (GC America, Alsip, IL, U.S.A.). The castings are returned as two separate units. The distal abutment teeth housing the matrix attachments for the Thompson dowel semi-precision attachment are inspected. A solder connection index is obtained with GC acrylic resin (GC America, Alsip, IL, U.S.A.). A pickup impression of the castings and edentulous areas is obtained for the lower denture fabrication using a custom tray border molded with green compound (Kerr Corp., Orange, CA, U.S.A.) and filled with Impregum impression material (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, U.S.A.). On the fourteenth visit, the laboratory returned the lower removable partial denture cast chromium cobalt framework with distal abutment #21 and 28 Thompson dowel semi-precision attachments. The patrix and matrix attachments of the Thompson dowel assembly and removable partial dentures are constructed of Jensen gold alloy (Jensen Dental, North Haven, CT, U.S.A.) soldered onto the prostheses. The abutments and framework are evaluated for fit of the major connector over the edentulous ridges. The removable partial denture design for the intaglio surface included a metal base over the retro-molar pads and mesh-work over the edentulous ridges7. The lingual plate is evaluated over the lingual surface of the castings, as well as the fit of the matrix into the patrix of the semi-precision attachments. A centric related jaw record is captured using Sil-Tech bite registration polyvinylsiloxane impression material (Ivoclar Vivadent, Amherst, NY, U.S.A.) and the case is returned to the dental laboratory. During the fourteenth visit, castings for copings #8, 9, and 10 are tried in. The distal of #8 and 10 have deep lingual rest seats for the minor connectors of the maxillary removable partial denture. A palatal strap was chosen for the major connector. Circumferential clasps are placed on teeth #2, 3, 14, and 15. After verifying the fit of the removable partial denture, the case is sent back to the dental laboratory with work authorization to add denture teeth in wax of the removable partial denture frame. The metal ceramic shade was chosen. At the fifteenth visit, the try-in of maxillary and mandibular removable prostheses at the wax-up stage is completed (Figure 9).

The fixed partial dentures are also evaluated at this time at the bisquebake porcelain stage. Vertical dimension of occlusion, labial drape, and aesthetics are all evaluated. Lastly, the patient’s speech was tested, especially with words using the “s” and “f” sounds. The work authorization for final glaze of the metal ceramic restorations and final processing of the RPDs is processed. The processed final prostheses are articulated in a Hanau articulator (Whip Mix, Louisville, KY, U.S.A.) and the centric relation is verified using three new bite registrations using green wax (Aluwax Dental Products Co., Allendale, MI, U.S.A.). Minor occlusal adjustments are necessary. On the sixteenth visit, provisional and transitional restorations are removed, and the maxillary and the mandibular fixed partial dentures are cemented with Optow Trial Cement (Waterpik, Fort Collings, CO, U.S.A.). The maxillary conventional RPD and mandibular semi-precision RPD are delivered (Figure 10). Evaluation of the patients’ occlusal relationships, denture base impingement, and aesthetics are done, followed by oral hygiene reinforcement. The patient is given postinsertion instruction and a follow up visit. In the follow up visit, the patient’s complaints are addressed. On the last visit, when all of the patients’ complaints have been addressed, all fixed partial dentures are removed. The abutment core structures are cleaned and final cement is used (Rely X, 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN. U.S.A.). Excess cement is cleaned off the margins. The post-op instructions are again given to patient and patient is put on a six-month recall for follow up.

Discussion

The 45-degree bevels were chosen to enhance the overall aesthetic appearance of the future restorations. Studies have shown that a bevel that brings metal and porcelain to the margin aides in good fit, contour, and color8. This type of margin also results in less plaque accumulation as well as creates less recession at the gingival-restoration interface. If the construction of a provisional restoration is hastily performed, it will not afford adequate protection and/or can result in damage to the prepared teeth and the supporting tissues9. The goal of these restorations was to restore satisfactory gingival adaptation, proper contours, cleansable embrasures, acceptable contacts, canine protected occlusal scheme, provision of space for pontics, and provision for acceptable phonetics. The concept of biologically acceptable provisional restorations demands that the prepared teeth be protected and the treatment restorations resemble the form and function of the final restorations. Henderson and Steffel stated: “Retainers for distal extension removable partial dentures, while retaining the appliance, must also act as stress breakers – they must be able to flex or disengage when the denture base moves tissue ward under functional stress”10. It is important to remember that when fabricating removable prostheses with distal extensions, there is the potential for the prostheses to become Class I cantilevers, especially when circumferential clasps are utilized for retainers11. A distal-extension prosthesis has multi-directional rotation, particularly when masticatory forces are applied to the distal-extension. These multi-directional rotations create damaging cantilever forces to the abutment teeth. Nonlocking, semi-precision rests permit prosthesis rotation and thereby reduce the torquing stresses transmitted to the abutment teeth. The most widely used non-locking intra-coronal attachment is the Thompson dowel rest, which contains two parts: a tapering recess and a well. The lingual surface of the crown is made flat and parallel with both the lingual surface of the opposite-side abutment casting and the lingual wall of the rest seat. The retaining metal projections that fit into the recesses will then be on the axis of rotation, so that they, and the two dowel rests, may rotate without any displacement of the retentive dimples. Lateral force transmission is provided by contact of the sides of the rest with buccal and lingual walls of the rest seat and by the rigid portion of the lingual clasp arm. When distal-extension ridges are present, a non-locking deep rest must be used to overcome the cantilever action which develops in a Class I lever system11. The try-in visit of both the fixed partial denture and removal partial denture setup is a crucial visit that provides valuable information concerning the placement of the restorations. The position of the anterior teeth controls not only the support of the lips, the visibility of the teeth, and anatomic harmony, but also provides definite guides (anterior guidance) for establishing jaw relations9. These crucial areas are essential to producing speech and are ones that patients will be most critical of, especially if they are missed. The patient is encouraged to pronounce “f” and “s” words12. Words with “f” are used to verify the position of the maxillary anterior teeth as they contact the vermillion border of the lower lip, aka the wet-dry lip line. Words with “s” (sibilants) are then used to match the lower anterior teeth to the maxillary anterior teeth. This step helps to identify and verify tooth position when anterior restorations are being fabricated. Loss of posterior teeth may result in the loss of neuromuscular stability of the mandible, reduced masticatory efficiency, loss of the vertical dimension of occlusion, and attrition of the anterior teeth13. It can also cause secondary occlusal trauma to the anterior teeth and worsen the integrity of the periodontal condition. Most of all, appearance and aesthetics are compromised. The traditional treatment modalities, including removable and fixed partial dentures, are commonly indicated for restoring vertical dimension and increasing occlusal contact in the posterior region. These treatment modalities also are less invasive and less costly in comparison to implant supported prostheses. If the removable partial denture is carefully implemented to the design principles and enhanced by the attachment system within the fixed partial denture, the patient acceptance of these prostheses is high. Long term care is compromised by prosthetic mechanical failures including tooth fracture, periodontal breakdown, and root caries14,15. The motivation of the patient to change one’s oral hygiene behavior in order to maintain the newly restored dentition is essential for the longevity of any prostheses. The biological price can be detrimental depending on the patient’s compliance.

Conclusion

This article demonstrates visit-by-visit that full mouth rehabilitation can be done on patients using traditional removable and fixed partial prostheses. Only a semiadjustable articulator with centric relation occlusion and thorough pre-treatment diagnostic wax-ups were used to navigate collapsed vertical dimension of occlusion and severe broken down teeth in the aesthetic zone.

Correspondence

Haig Rickerby: hhr1@nyu.edu

Steven S. Lee: slee952@verizon.net

References

1. Dawson P. Evaluation diagnosis and treatment of occlusal problems. 1989, Mosby.

2. Parker MW. The significance of occlusion in restorative dentistry. Dental Clinics of North

America 1993;37(3):341-351.

3. Cordray FE. Three-dimensional analysis of models articulated in the seated condylar position from a deprogrammed asymptomatic population: a prospective study. Part 1. American Journal of Orthodontics Dentofacial Orthopedics 2006;129(5):619-630.

4. Vierheller PG. A functional method for establishing vertical and tentative centric maxillomandibular relations. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 1968;19(6):587-593.

5. Ward BL, Osterholtz RH. Establishing the vertical relation of occlusion. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 1963;13(3):432-437.

6. Verri FR, Pellizzer EP, Mazaro JVQ, de Almeida EO, Antenucci RMF. Esthetic interim acrylic resin prosthesis reinforced with metal casting, Journal of Prosthodontics 2009;19(6):541-544.

7. Weintraub GS. Review of removable partial denture components and their design as related to maintenance of tissue health. Dental Clinics of North America 1985;29(1):39-56.

8. Panno FV. Evaluation of the 45-degree labial bevel with a shoulder preparation. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 1986;56(6):655-661.

9. Fox CW. Provisional restorations for altered occlusions. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 1984;52:567-572.

10. Zinner ID. Semi-precision rest system for distal-extension removable partial dentures. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 1979;42:10:4-11.

11. Zinner ID. A modification of the Thompson dowel rest for distal-extension removable partial dentures. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 1989;61(3):374-378.

12. Murrell G. Phonetics, function and anterior occlusion. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 1974;32(1):23-31.

13. Budtz-Jorgensen E. Restoration of the partially edentulous mouth-a comparison of overdentures, removable partial dentures, fixed partial dentures and implant treatment.The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 1996;24(4):237-244.

14. Walton TR. An up to 15-yr longitudinal study of 515 metal-ceramic FPDs: Part 2. Modes of failure and influence of various clinical characteristics. International Journal of Prosthodontics 2003;16(3):177-182.

15. Libby G, Arcuri MR, LaVelle WE, Hebl L. Longevity of fixed partial dentures 1997;78(2):127-131.